Éastre 💐

ǽringes síþbode

Éastre is a widely-discussed, and widely-misunderstood, Old English goddess. Only attested in one 8th century source, much ink has been spilled on this figure with etymological ties to the east and the dawn, but whose name in usage most often designates Passover or Easter.

📜 Bede’s Eostre

🌅 Etymology

👩👩👧 Mātrōnae Austriahenae

🗺️ Place names?

📛 Personal names

📍 A local Kentish goddess?

💫 A popular goddess

📝 A quick summary

🍂 Notes & Acknowledgements

📚 Bibliography

— C. Ryan Moniz

winter mmxxiii

updated harvest mmxxiii

Disclaimer: This piece merely reflects my own understanding of this deity based on my research and experiences.

📜 Bede’s Eostre

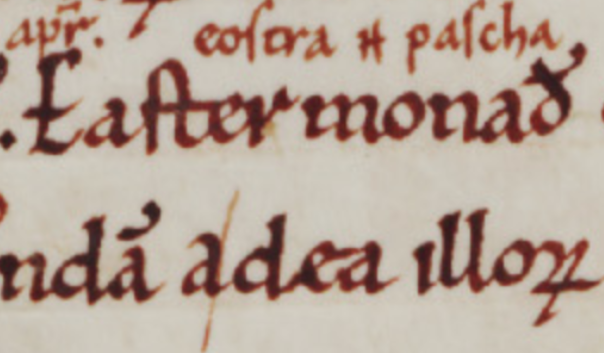

In Dē temporum ratiōnē, the same 725 text which is our main source for Hréðe, the Venerable Bede provides an explanation for the Old English name of ‘April’:

🙞 Eosturmonath quī nunc paschālis mēnsis interpretētur quondam ā deā illōrum quae eostre vocabātur et cui in illō fēsta celebrābant nōmen habuit ā cuius nōmine nunc paschāle tempus cognōminant· consuētō antīquae observātiōnis vocābulō gaudia novae solemnitātis vocantēs·

«Eosturmonath, which is now translated as ‘the Paschal month,’ formerly named for their goddess called Eostre, and by whose name the paschal time is now called, referring to the joys of the new ceremony with the customary designation of the ancient observance.»

— Dē temporum ratiōnē ·XV· ‘Dē mēnsibus anglōrum’

As explored on the above-linked Hréðe page, the manuscript evidence attests to a probably n-stem feminine noun Éastre.❦1Cotton MS Vespasian B vi, f.20r· (9th c); Royal MS 15 B xix f.64v· (10th-11thc); Oxford, St. John’s College MS 17,, f.76v· (ca 1110); Royal MS 13 A xi, f.49r· (11-12th c); Royal MS 12 D iv f.54v· (early 12th c); Cotton MS Tiberius E iv, f.60v· (early 12th c) The early manuscripts where the name is written with ⟨eo⟩ or ⟨aeo⟩ rather than ⟨ea⟩ are likely reflective of Bede’s local Northumbrian dialect: the standard éa, pronounced [æːɑ] in other dialects, evolved from an original Germanic diphthong au, with an intermediary stage of being pronounced something like [æːo] reflected in the spelling ⟨aeo ~ æo⟩. In later Northumbrian, this diphthong was often merged with éo (from earlier Germanic eu), making the two indistinguishable, whereas the distinction is usually maintained in other dialects.

There is also some variation with the spelling of the month, where there are some manuscripts with a spelling eostur-/eastur- and others with eoster-/easter-.

Outside of Bede’s explanation in this text, we see éaster, éastre, éostru, éastran, éastron, and other variants most typically refer to Passover. it also is used to refer to the Christian Easter, and occasionally to spring in general. Compounds like éastertíd (or éastortíd) are also attested, where the first element refers to Passover or Easter.

This wide use of the name for the holiday is not only found in prose, but also in poetry. A notable example can be found in the poem The Descent into Hell which, when narrating the finding of Jesus’ tomb, includes the alliterative lines:

🙞 wéndan þæt hé on þám beorge bídan sceolde

ána in þǽre éasterniht· húru þæs óþer þing

wiston þá wífmenn þá hý on weg cyrdon·

«They thought that he would have to lie in the tomb alone on that Passover night. However, the women knew something very different when they came back on their path».

— The Descent into Hell 14a-16b

The form of éaster/éastor which appears most frequently in compounds is evidently a strong noun; this is probably also the case for the Northumbrian variant éostru. The form éastre (which, in West Saxon especially, is almost always written in the plural éastran or éastron) is an n-stem feminine, just as the name given for the goddess by Bede.

If we are to take Bede at his word, it must be the case that, despite having originally been the name of a goddess, it became thoroughly and widely associated with Passover already by his time. The reason he provides for this transition — that being the timing of the celebrations — might suggest that the name of the goddess was in some way tied to the timing of the observance.

🌅 Etymology

The clearest cognates to the terms provided by Bede are the Old High German ôstarun, which glosses Latin ⟨pascua⟩ (= pascha ‘Passover’) ❦2Stifsbibliothek MS 911, 226· Abrogans (8th c.), and the Frankish ôstarmanoth ‘april.’❦3Einhardus Vīta Karolī magnī (9th c.) Jakob Grimm believed that these were cognate with Éastre and éastormónaþ, reconstructing an Old High German theonym *Ôstara; Éastre and *Ôstara in turn would suggested a Proto-West-Germanic *Austrā (← Proto-Germanic *Austrǭ, related to the adjective *austraz ‘east(ern)’).

However, it is also possible that these terms in Old High German and Frankish reflect loans from Old English — while, formally, these terms appear to be cognates (showing a correspondence of Old English éa :: Old High German ô), it is possible that the etymological transparency between these words and ‘east(ern)’ (Old English éast :: Old High German *ôstar) led to this kind of borrowing. The possibility of a borrowing from Old English tradition is likely here when the limited scope of these terms (for Passover, Easter, and the month of April, equating to the narrowest scope of the Old English use) is considered along with the fact that much of the Christian conversion of these regions was carried out by missionaries from England in the 7th-9th centuries.

Even if the other terms in West Germanic are just Old English loans, internal and comparative reconstruction still suggests a Proto-Germanic origin of *Austrǭ for the Old English form éastre. This Proto-Germanic form, related to attested words for ‘east’ in other Germanic languages, fits neatly into the mold of the Proto-Indo-European root extension *h₂eus·ro/eh₂-; this root extension also yields Proto-Germanic *austra- ‘east,’ and Proto-Baltic *aušra ‘dawn,’ whence comes the Lithuanian goddess Aušrinė ‘dawning’ associated with the morning star❦4cf. *h₂eus·i- → Proto-Germanic *Auziwandilaz ‘morning star’ and the sunrise.❦5A similar root extension *h₂éus·r-/*h₂eus·ér- yields Greek αὔρᾱ aúrā ‘morning air’ and ᾱ̓ήρ āḗr ‘air, mist.’ Another root extension *h₂éus-os- is the source of the Vedic dawn goddess उषाः Uṣā́ḥ, the ancient Greek dawn goddess Ἠώς Ēós, and the Latin dawn goddess Aurōra.

In the Lithuanian mythic tradition, the morning-star goddess Aušrinė (whose name has the closest etymological link to Germanic Éastre) is given the role of preparing the way for the sun goddess (Saulė) to enter the sky. Vytautas Tumėnas (2018) has recently connected her with the traditional “comb/rake” patterns found in Lithuanian textiles and in Neolithic solar depictions.❦6Tumėnas 2018 She is also a goddess of beauty, love, and weddings, and Tumėnas proposes a connection between her and the traditional combing and braiding of a bride’s hair before a wedding; this connection is attested in folk songs, such as this one which contains the line iš kaselių saulė teka ‘the sun is rising from her braids.’❦7Tumėnas 2018, p 384

The Proto-Indo-European root *h₂éus- ‘dawn, east’ has many other root-extensions and derivatives, but those aforementioned seem to be the most connected with dawn or morning goddesses. If Bede was mistaken about the origin of the month’s name deriving from a goddess named Éastre, it would seem he made a very serendipitous mistake, considering it is (formally) uncannily close to the Lithuanian goddess, and from the same root as several other Indo-European dawn goddesses. This does not guarantee a connection between these figures and the one mentioned by Bede, but it does at least give reason for pause before completely discounting Bede’s testimony.

👩👩👧 Mātrōnae Austriahenae

In 1958, more than 150 Roman inscriptions were found in Morken-Harff (near Cologne) dating to the late 2nd to early 3rd century. All but one of these inscriptions were dedicated to Mātrōnae Austriahenae. While the name element -henae, found in several of the Mātrōnae titles, is now believed to be an originally Celtic suffix used in ethnonyms, the former element austria- is most likely cognate with Éastre, or at least with the probably-connected Germanic words for ‘east’. While this does not prove that these figures are related, it at least indicates that there was another, likely Germanic or Celto-Germanic, goddess cult whose name included this root.

🗺️ Place names?

There are at least three names ❦8The name of Austerfield in South Yorkshire is widely believed to be unrelated; although there one instance of the town being spelled ⟨Eostrefeld⟩, most other spelling variants point instead to an original Éowestrefeld ‘sheepfold-field’ (of which Eostrefeld was likely a contracted form) which formally appear to have an element similar to Éastre. The northernmost is Eastrington in East Yorkshire which, according to Richard Sermon❦9Sermon 2022, is earliest attested in the form ⟨Eastringatun⟩. The second is Eastrea in Cambridgeshire and has its earliest attestation in the form ⟨Estrey⟩. The southernmost is Eastry in Kent (which likely includes the rare archaic element gé ‘district,’ cf. Surrey ← Súðergé), for which there there are a dozen attestations ranging in form from Eastrgena at the earliest (late 8th century) and Eastrige at the latest (early 11th century)❦10Brooks & Kelly (ed) 2013; Sermon 2022; there is variation in the Old English records of Eastry between forms with eastor-, easter-, and even eastr-.

Apart from the use of an element east(o/e)r-, the other unifying factor with these locations is a geographical one: while they are located in different historical regions of england, they are all located in the east. A simple explanation, then, could be that these names are derived from the comparative adjective éast(e)ra ‘further east.’ Philip Shaw (2011)❦11Shaw 2011 argues against this, proposing instead an otherwise-unattested *éastor ‘eastern’ (not to be confused with attested éastor-/éaster- found in the Passover compounds discussed above), hinging on 3 attestations of Eastry with a spelling of ⟨eastor-⟩; however, as mentioned above, and emphasized with force by Sermon (2022), these 3 -tor- spellings are accompanied by 2 spellings with -ter- in the same charter, 3 spellings with -ter- elsewhere, and 4 spellings with no vowel at all (i.e. eastr-), including the earliest attestation in 788.❦12Sermon 2022; Brooks & Kelly (ed) 2013 Moreover, alternation between unstressed -or-, -er-, and -r- is found in abundance throughout Old English spelling.

Even ignoring the obvious variation between the spellings of these forms, Sermon (2022) notes, the semantic difference between éast(e)ra ‘further east’ and *éastor ‘eastern’ is negligible when it comes to the origin of these names — in either case, the most parsimonious explanation is that these places were named based on their eastern location. While a connection between them and the goddess mentioned by Bede is not impossible, it is also not at all necessary to explain them.

📛 Personal names

In his Historia abbātum, Bede records a 7th century abbot named ⟨Eosteruini⟩, which seems to be a Northumbrian variant of a name Éasterwine. The 9th century Liber vītae (confraternaty book) of Durham, also found in Northumbria, registers 3 figures with apparently equivalent names in different spellings: ⟨Aesturuini⟩, ⟨Aeostoruini⟩, and ⟨Eosturuini⟩; this book also records an abbess named ⟨Aestorhild⟩. On the surface, these names appear to be potential theophoric names like Óswine, Ælfhild, &c. (cf. also Frankish Austrechild). However, Shaw (2011) argues that the notion that these are theophoric names is “unacceptable on linguistic grounds” because they all demonstrate a form with -tor/tur- and thus are “not the feminine form used for the goddess’s name.”❦13Shaw 2011, p 60 As Sermon (2022) argues above, this is not a convincing argument, especially considering the earliest forms of the month name that Bede explicitly connected with the goddess are also spelled with -tor/tur-, and (as discussed above) attestations for forms like éastortíd ‘Paschal time’ are readily found.

Furthermore, a theophoric meaning of ‘friend of Éastre’ for a name like Éasterwine is better paralleled (e.g. Ælfwine ‘elf-friend,’ Óswine ‘god-friend’) than a meaning of ‘eastern friend’ (or ‘Passover friend’), and arguably makes more logical sense than these alternative meanings.

📍 A local Kentish goddess?

In his account, Bede explains that the transfer of the goddess’s name to the Paschal month was motivated by the coincidental timing of her typical celebrations with that of the christian easter. Sermon (2022) emphasize that, as Bede reckons, the beginning of Éastermónaþ would fall on or around the spring equinox,

“when the sunrise and nearest full-moonrise generally appear […] in their most easterly positions on the horizon […] furthermore, this full moon would have coincided with the Paschal full moon used to calculate the Christian date of Easter.”❦14Sermon 2022

The timing of the Éastre-celebrations reported by Bede, taken with the etymological connection to ‘east’ and to other indo-european dawn goddesses has led many who take Bede’s report seriously to postulate that Éastre, too, was a goddess associated with the dawn and spring.

Shaw (2011) argues instead that this goddess was local to Kent, making an analogy to the possibly local Mātrōnae Austriahenae found in the Lower Rhine. His argument primarily relies on his reconstruction of *éastor as the origin of the Kentish place-name Eastry discussed above, and the fact that some of Bede’s informants for his Historia Ecclēsiastica were from Kent, which could open up the possibility that knowledge about Éastre recorded in (the separate work) Dē temporum ratiōnē could also have been influenced by a Kentish source. He suggests in particular that the spelling of ⟨eo⟩ in Bede’s account of the goddess and month point to influence from “a written source from outside his own locality.”❦15Shaw 2011, p 65 However, as discussed above, Shaw’s reconstructed *éastor is unnecessary to explain this place name, and the spelling with ⟨eo⟩ is a widely-noted indicator of the Northumbrian dialect (i.e. Bede’s own), with no clear indication towards Kent.

Shaw also argues against Éastre having been a goddess related to dawn on the basis that Bede never makes explicit reference to dawn.❦16Sermon (2022) comments, however, that Bede does not make any explicit reference to her having been a deity local to Kent, either He adds that, unlike some other Indo-European languages where words for ‘dawn’ and ‘east’ are connected semantically, that same connection is not clear in Germanic languages (even if they were linked etymologically). However, Sermon (2022) remarks that this did not mean a logical connection between between the east and the dawn was not still salient for Germanic language speaker, pointing to the example of Gúþlác:

óþþæt éastan cwóm

ofer déop gelád dægrédwóma

«until, out from the east, the rush of dawn came over the deep path».

— Gúþlác 1292b-1293b

Indeed, if we are to take Bede at his word, a goddess by the name Éastre celebrated at the spring equinox with a transparent connection to attested words for ‘east’ would suggest a strong connection indeed between the east and the dawn in the consciousness of the early English. Even in the event that Bede is mistaken, there would still remain the clear connection between the Paschal month and spring equinox with a word with some sort of relation to ‘east.’ Either of these interpretations are more firmly grounded in extant evidence than Shaw’s proposed Kentish cult.

💫 A popular goddess

Since the publication of Grimm’s 1835 theory regarding a German goddess *Ôstara, this goddess has spread and been taken up into popular modern folklore in the German and English-speaking world (and beyond). As early as the late 19th century, we find folklorists connecting early modern Easter practices with the goddess, such as in the story of a bird changed into a hare (attributed to Germans in Germany and Pennsylvania) ‘by the goddess Ostara.’❦17Walsh &al (ed) 1889, p 65 The name ‘Ostara’ was eventually given to the Wiccan celebration of the spring equinox by Aidan Kelly in 1974❦18Kelly 2017, which in turn has led to an increased awareness of the figure. All manner of misinformation has been spread relating to this goddess, in spite of researchers’ concerted efforts, but that topic is better treated elsewhere; for more on this, see this article from Lay of the North Sea.

📝 A quick summary

Below is a quick summary of some of the key points presented in the earlier sections of this page:

- • Bede records that the Old English name for April, ⟨Eosturmonath⟩, is so named because a goddess ⟨Eostre⟩ was celebrated during that time.

- • The term éaster/éastor is used alone and in many compounds to refer to Passover and Easter throughout Old English literature.

- • Several Indo-European dawn goddesses are attested with names that formally suggest a cognate relationship with both Ëastre and with ‘east,’ particularly the Lithuanian goddess Aušrinė whose name derives from the same Indo-European root extension (if it is indeed cognate).

- • A Mothers cult with a name containing a likely cognate element Austria- appears in the Lower Rhineland.

- • There are 3 place names in eastern England which appear to contain an element éast(e/o)r-, but this is most likely a reference to their eastern location.

- • There are at least two names (attested a collective 4 times), Eosterwine and Æstorhild, which appear to be theophoric names including Bede’s Eostre as their first element.

- • Manuscript evidence points to Northumbrian documents being the earliest attested, which makes sense considering our only direct source for the goddess is Bede, a Northumbrian.

🍂 Notes & Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Ælfwald, Nico Solheim-Davidson, and eoforwine for helping me find some of these resources.

- ❦1 Cotton MS Vespasian B vi, f.20r· (9th c); Royal MS 15 B xix f.64v· (10th-11thc); Oxford, St. John’s College MS 17,, f.76v· (ca 1110); Royal MS 13 A xi, f.49r· (11-12th c); Royal MS 12 D iv f.54v· (early 12th c); Cotton MS Tiberius E iv, f.60v· (early 12th c)

- ❦2 Stifsbibliothek MS 911, 226· Abrogans (8th c.)

- ❦3 Einhardus Vita Karoli magni (9th c.)

- ❦4 cf. *h₂eus·i- → Proto-Germanic *Auziwandilaz ‘morning star’

- ❦5 A similar root extension *h₂éus·r-/*h₂eus·ér- yields Greek αὔρᾱ aúrā ‘morning air’ and ᾱ̓ήρ āḗr ‘air, mist.

- ❦6 Tumėnas 2018

- ❦7" p 384

- ❦8 The name of Austerfield in South Yorkshire is widely believed to be unrelated; although there one instance of the town being spelled ⟨Eostrefeld⟩, most other spelling variants point instead to an original Éowestrefeld ‘sheepfold-field’ (of which Eostrefeld was likely a contracted form)

- ❦9 Sermon 2022

- ❦10 Brooks & Kelly (ed) 2013; Sermon 2022

- ❦11 Shaw 2011

- ❦12 Sermon 2022; Brooks & Kelly (ed) 2013

- ❦13 Shaw 2011, p 60

- ❦14 Sermon 2022

- ❦15 Shaw 2011, p 65

- ❦16 Sermon (2022) comments, however, that bede does not make any explicit reference to her having been a deity local to Kent, either

- ❦17 Walsh &al (ed) 1889, p 65

- ❦18 Kelly 2017

📚 Bibliography

- 🔖 Brooks, NP & Kelly, SE (ed) 2013· Charters of Christ Church, Canterbury, Part 1: Anglo-Saxon Charters.

- 🔖 Kelly, A 2017· “About naming Ostara, Litha, and Mabon,” Including Paganism

- 🔖 Sermon, R 2022· “Eostre and the Matronae Austriahenae.” Folklore 113

- 🔖 Shaw, P 2011· Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World: Eostre, Hreda, and the Cult of Matrons

- 🔖 Tumėnas, V 2018· “Signs of the Morning Star Aušrinė in the Baltic Tradition: Regional and Intercultural Features,” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 18,4

- 🔖 Walsh, WS &al (ed) 1889· American Notes and Queries, vol. 3